Meet Myron Lard: First to Investigate Soil Samples in Colfax, Louisiana, and East Palestine, Ohio

October 15, 2024

For 15 years, the LSU Superfund team has been protecting communities from pollution.

“For me, it’s all about using science for community benefit,” said Myron Lard.

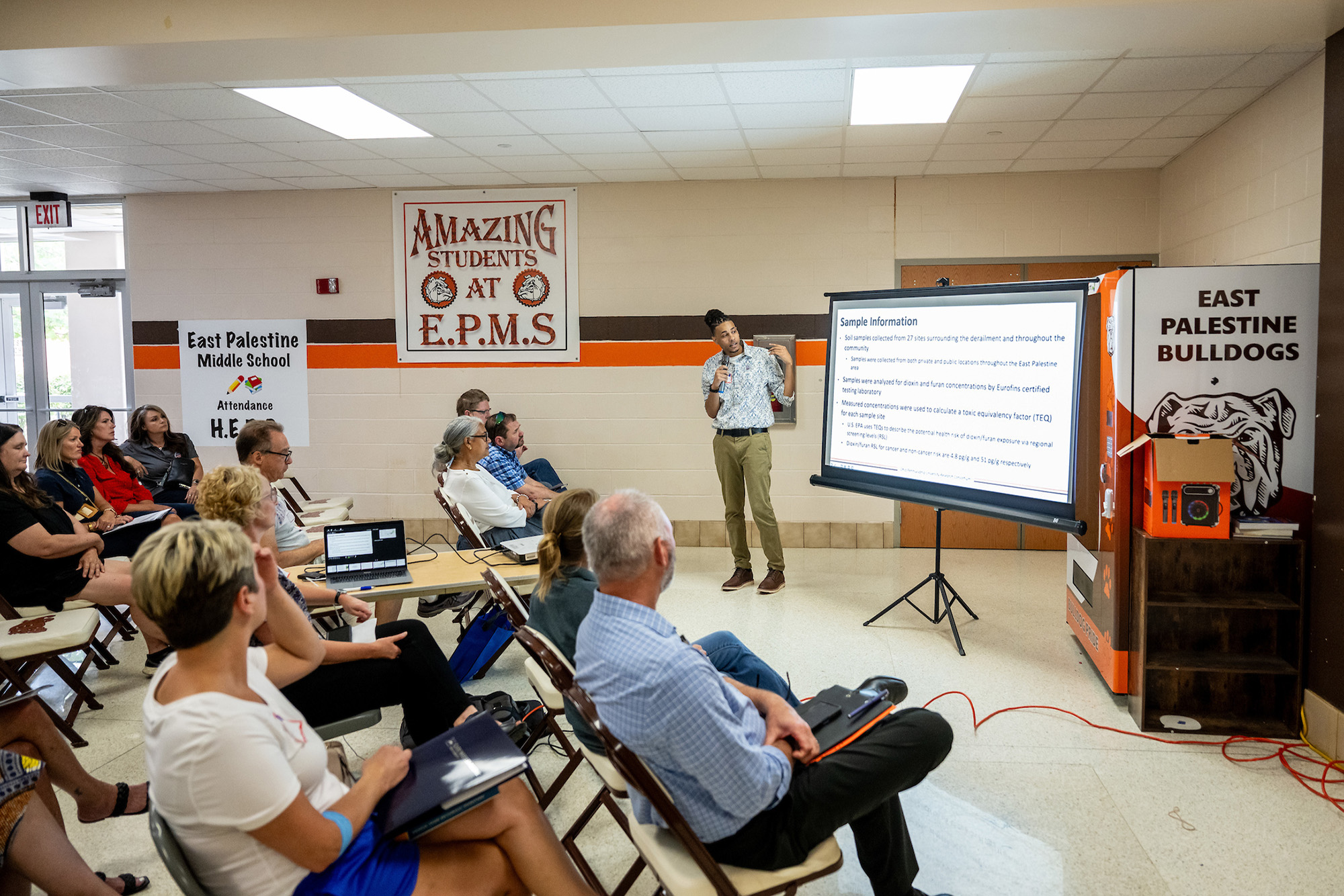

– Image courtesy of Kent State University

Doctoral student in chemistry Myron Lard joined LSU to help advance the science on environmentally persistent free radicals, a dangerous pollutant found in air, soil, and homes all over the world. Starting in the lab on LSU’s flagship campus, studying model clays, Lard soon found himself working alongside residents and communities to collect soil samples across the state. Then, when a Norfolk Southern freight train carrying hazardous chemicals derailed and caught fire in East Palestine, Ohio, he was first on the field to collect soil samples and use knowledge gained in Louisiana to help people there.

“It was primarily the work we did together in Colfax, Louisiana, that inspired me to get involved in East Palestine,” Lard said. “I saw an opportunity to be useful. We could lend our expertise on environmentally persistent free radicals, build a research team, and quickly get information to the community.”

Many of the train cars in the 2023 Norfolk Southern train derailment in East Palestine, Ohio, contained hazardous materials, including vinyl chloride, butyl acrylate, and isobutylene. Some cars spontaneously caught fire. Three few days later, Norfolk Southern conducted a controlled burn of the rest. “If there’s one thing we know based on our research in Colfax, Louisiana, it’s that whenever you burn hazardous chemicals outdoors, it impacts the surrounding community,” Myron Lard said.

– Photo courtesy of Kent State University

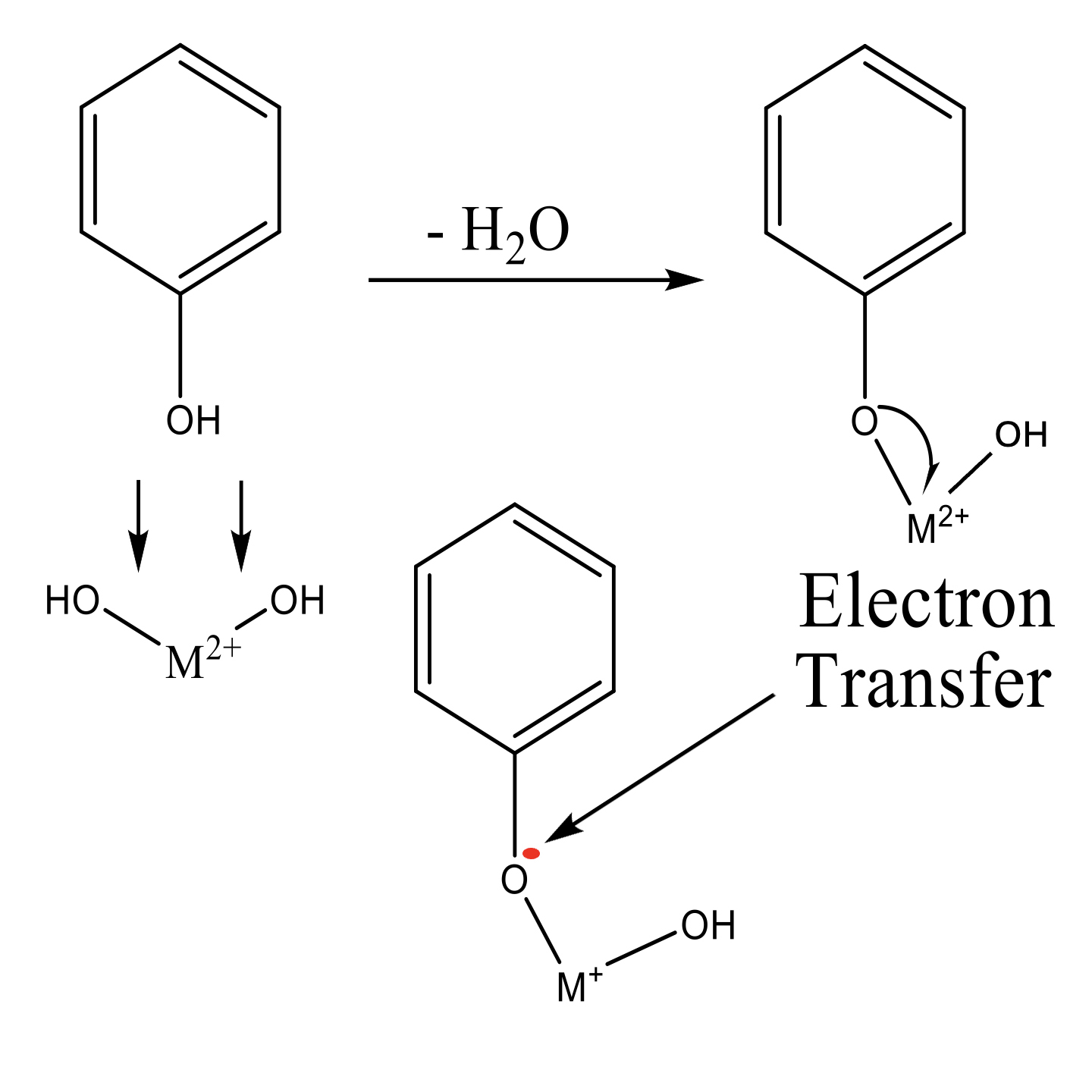

Since 2009, LSU’s Superfund Research Program, of which Lard is a member, has been the primary source of the emerging global science on environmentally persistent free radicals, which are created through combustion and exist in everything from car exhaust to cooking fumes to wildfires.

“They especially come from the burning of toxic chemicals and hazardous waste,” said LSU Professor Stephania Cormier, a toxicologist who leads the Superfund team. “Our research has shown impacts on both lung and cardiovascular health, how it can decrease the immune system’s ability to fight off infection, and how children are particularly vulnerable.”

“Myron Lard is not only helping to protect communities but advancing the fundamental science on how environmentally persistent free radicals are formed and how to destroy them,” Cormier added.

Environmentally persistent free radicals can survive in soil and on surfaces for months or years. Because of their unpaired electrons, they’re also reactive. Myron Lard’s research showed high levels of environmentally persistent free radicals as well as high levels of dioxins and furans near the Norfolk Southern derailment site, suggesting the dangerous radicals—the main focus of the LSU Superfund Research Program—could be an initial indication of dioxins and furans, which can cause cancer.

Lard brought soil samples from East Palestine back to the Cook research lab at LSU where he dried and ground them. He then checked for environmentally persistent free radicals using electron paramagnetic resonance, a type of spectroscopy that can detect the radicals’ signature feature: unpaired electrons. He also sent off samples to measure cancer-causing dioxins to another, certified lab. Almost half of the samples, 48%, came back indicating cancer risk. For the first time, Lard was able to make a new connection between environmentally persistent free radicals and dioxins using real-world samples.

“Myron’s field samples show a correlation between environmentally persistent free radicals and dioxins and furans that suggests a link between them,” said Robert Cook, professor of chemistry and member of the LSU Superfund Research Program. “A possible cause for this link is the conversion of the former into the latter.”

“Myron’s focus on soils has woven our group’s two areas of research: furthering our understanding of fundamental chemical processes of environmental consequence through a bottom-up approach, and our detection and study of pollutants in real-world environmental samples through a top-down approach,” continued Cook, whose lab at LSU studies environmental pollutants in everything from pastures, fields, and forests to rivers, lakes, and swamps. “Myron’s contributions have clearly shown how this multiscale approach—from nanometers to kilometers—allows for laboratory findings to be directly applied to our understanding of environmental health consequences.”

Lard was recently selected, as one of only five students in the nation, to present his research at the Harvard University Chemistry Future Leaders Symposium. He’s also shared data at community meetings in both Louisiana and Ohio.

LSU doctoral student in chemistry Myron Lard has presented his research on toxic compounds found in soil at the Harvard University Chemistry Future Leaders Symposium and community meetings in Louisiana and his native Ohio, including in East Palestine after the Norfolk Southern train derailment. Lard chose to pursue his Ph.D. at LSU after receiving his bachelor’s degree in chemistry from Kent State University, about an hour’s drive from East Palestine.

“You’d think only a few people would show up to hear scientists talk about data,” Lard said. “But it’s been incredible. People are engaged and want to learn and understand what’s going on, because this stuff affects their lives, right? I came to LSU to be a chemist, but it’s been a very cool experience to interact with the community as much as I have.”

“As scientists and researchers, I think it’s important we show up, show our face, and be a voice though the noise,” Lard continued.

“ In situations like Colfax and East Palestine, things can get political and all kinds of messy, so it can be hard for people to know what to really trust. That’s why university research is so important. We provide data people can feel confident about, so they can make the best decisions about their lives and health. ”

Colfax, Louisiana, where Lard began collecting soil samples, is home to the only commercially operating open-burn, open-detonation hazardous waste facility in the nation. The LSU Superfund team continues to collect environmental data together with community members and residents like Brenda Vallee, who initiated the collaboration in the first place.

“When I became aware of the environmental situation in which I live, my first concern was for my family,” Colfax resident Brenda Vallee said. “Working with the LSU Superfund Research Program, we’re finding out more about our own area, about ourselves, and getting answers to questions.”

Particulate matter in air pollution, which is a primary vehicle for environmentally persistent free radicals, has in recent years become the world’s largest contributor to the global disease burden. Air pollution is now linked to 1 in 8 deaths worldwide and a bigger risk factor than smoking, obesity, and diabetes. People who live in the most polluted areas see their lives cut short by roughly two years on average.

“When I learned about the research taking place at LSU, LSU became an immediate frontrunner for me, for where to do my Ph.D.,” said Lard, who is in the process of defending his thesis. “Since then, I’ve found a passion for this research I didn’t expect. For me, it’s all about using science for community benefit.”

Learn MORE ABOUT Myron Lard’s work in Colfax, Louisiana

Learn more about Myron Lard's work in East Palestine, Ohio

Next Steps

Let LSU put you on a path to success! With 330+ undergraduate programs, 70 master's programs, and over 50 doctoral programs, we have a degree for you.